Source: Mid-Day

Mountaineer Anurag Maloo’s recent rescue brings to the forefront the many challenges of food, oxygen, weather, fitness and expertise that form the roulette of their lives

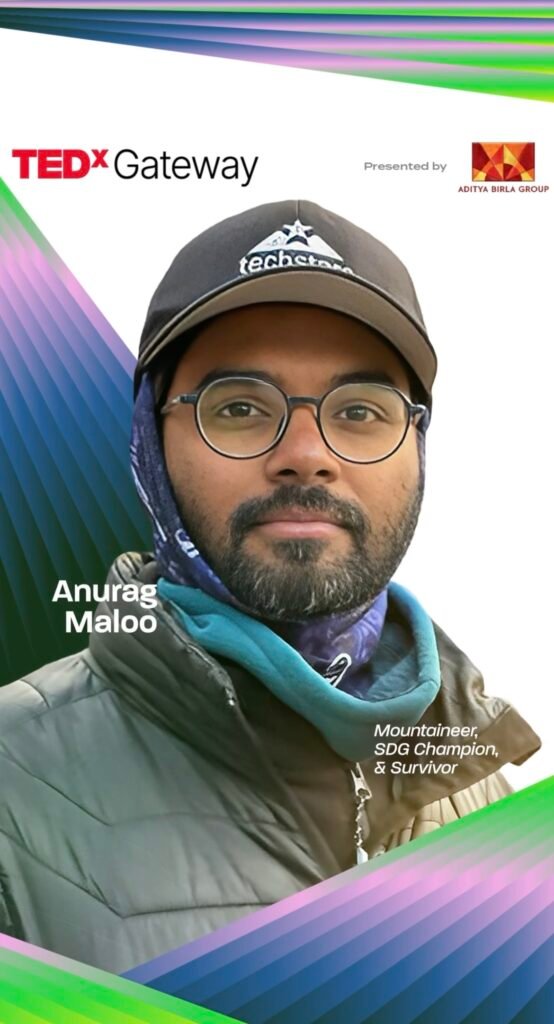

Anurag Maloo, entrepreneur and renowned mountaineer, was rescued alive from Mount Annapurna. Photo Courtesy: Obtained through special permission

On April 20, Anurag Maloo, entrepreneur and renowned mountaineer, was rescued alive from Mount Annapurna, the tenth highest mountain in the world, after being missing for over 60 hours. The miraculous rescue came just two days after another mountaineer, Baljeet Kaur, also went missing from another point at Annapurna and was found alive on April 16 and rescued on April 18. A third climber from the same expedition, Noel Hanna from Ireland, was lost to the tricky rocks, and mourned across the globe.

As heartening as Maloo’s rescue is, the incident drew attention towards the perils faced by mountaineers on pursuits as well as the need for surgical precision and supreme fitness. Several hardcore mountaineers that mid-day spoke to said that the mountains are a fickle passion, and any step could be your last.

Anand Shinde, a Head Constable with the Mumbai Police who is also an avid mountaineer, said altitude and weather are the biggest challenges, and that the descent is much riskier than ascent. All the three climbers at the Annapurna fell during descent.

“On the way down,” Shinde says, “your energy levels are lower, you often don’t have enough food and the oxygen is depleting. Mentally, too, the long and hard climb takes its toll. This is when most accidents occur, and when all your senses need to be on high alert.”

He recalls his own narrow escape while descending Sasar Kangri peak in 2018, a mountain at the easternmost end of the Karakoram range in Siachen. Shinde was on an expedition with Pemba Sherpa, a celebrated mountaineering guide who had scaled Mount Everest eight times.

“I finished the climb and started back down,” recalls the officer posted with the Marine Drive police station, “The weather changed suddenly and radically, so much so that we were sweating at 6,500 meters. The heat created hidden crevasses under the ice, and all the spots usually marked safe were suddenly dangerous. On my way to the camp, I stepped on a patch of ice, and it cracked. I was stuck up to my waist in the crevasse for hours, but managed to pull myself out.”

Anand Shinde, a head constable with the Mumbai Police at Marine Drive police station, is also an avid mountaineer. Photo Courtesy: Sameer Markande

Sherpa plummeted into a crevasse at the almost exact spot the next day. The Indo Tibetan Border Police scoured the entire area for over a month, and even found his backpack, but not him.

Shinde also recalls the case of Anjali Kulkarni, a Thane resident who had gone on an expedition to Everest with her husband, Sharad. On her way to the summit, while combating depleting oxygen and extreme weather, Anjali fell close to Camp IV. Sharad later made a documentary to highlight the growing concern of overcrowding at Everest due to commercial climbers—those with scant training and experience who want to scale the peaks with the help of Sherpa guides. A picture that went viral the same year shows nearly 200 climbers in a long line waiting to climb to the summit. Sharad is currently on a mission to conquer the seven highest summits in the world as a tribute to Anjali.

The grouse about commercial climbers is often voiced by old-school mountaineers. Rajesh Gadgil, a Borivli-based businessman who has been a mountaineer since the age of 23, talks of climbers who couldn’t even use a crampon properly. A crampon is attached to a climber’s shoes for better traction on ice, and is part of every climber’s basic training course.

Gadgil says that such people wouldn’t last a day on their own, without a Sherpa. A purist, he even refuses to refer to mountaineering as a ‘sport’ because he feels it is not a game. Dipping into his own experiences, Gadgil highlights a risk associated with a factor few people think of—food.

“In the mountains,” he informs, “you calculate every gram of weight you carry, which includes food. If you lose your way, you run out of food before you reach a camp or meet a support team. In 2013, six of us were traversing the Karakoram range on a 30-day expedition; we would rendezvous with our support team every 10 days to stock up on supplies. On the last day of the second 10-day phase, we lost our way to the rendezvous spot. We had only breakfast and were continuously on the move for the next seven hours. We were delirious and ready to drop; sheer survival instinct kept us going.”

Fortunately, the support team too had lost their way due to poor visibility, and Gadgil’s team ran into them by accident. The meal that followed, he says, was the best meal of his life.

Maloo has been shifted to a hospital in Kathmandu and while his condition remains critical, his family is sure that he is going to come back to them. “He still needs all your blessings,” Maloo’s brother Sudhir said on April 20 in a WhatsApp voice note he sent to a 600-member group of his brother’s friends and well-wishers. “He is very, very critical but he is a fighter. He is going to make his comeback and it will be grand. Take my word for it.”